Supreme Court Audio Tapes

The U.S. Supreme Court began recording oral arguments in October 1955 on reel-to-reel tapes that it would later send to the National Archives. Normally, such tapes are considered “masters” which are stored in special climate-controlled rooms and which no one is permitted to touch – unless of course they work there.

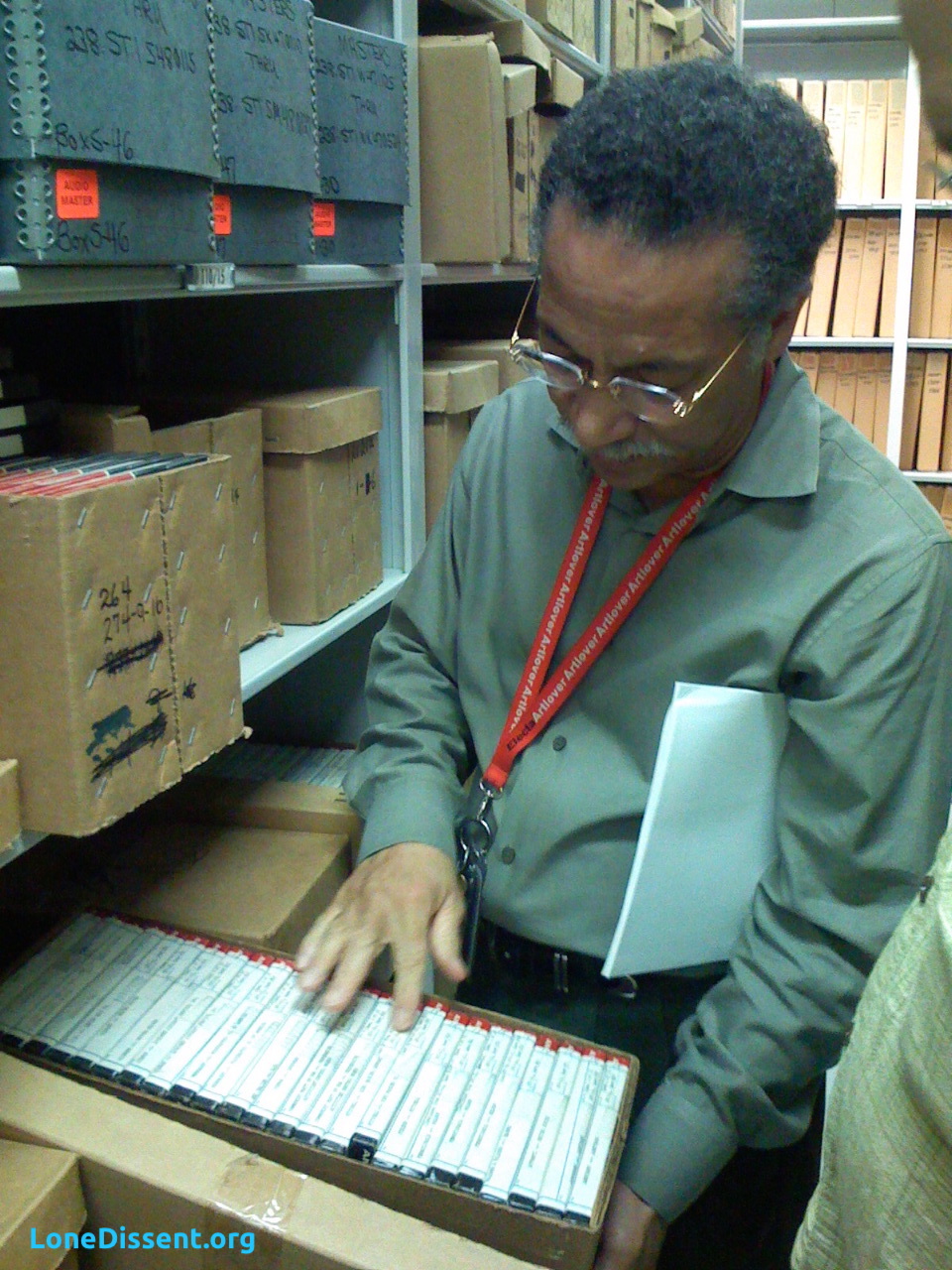

Charles DeArman, retired NARA archivist, holding a box of U.S. Supreme Court master tapes (July 2007)

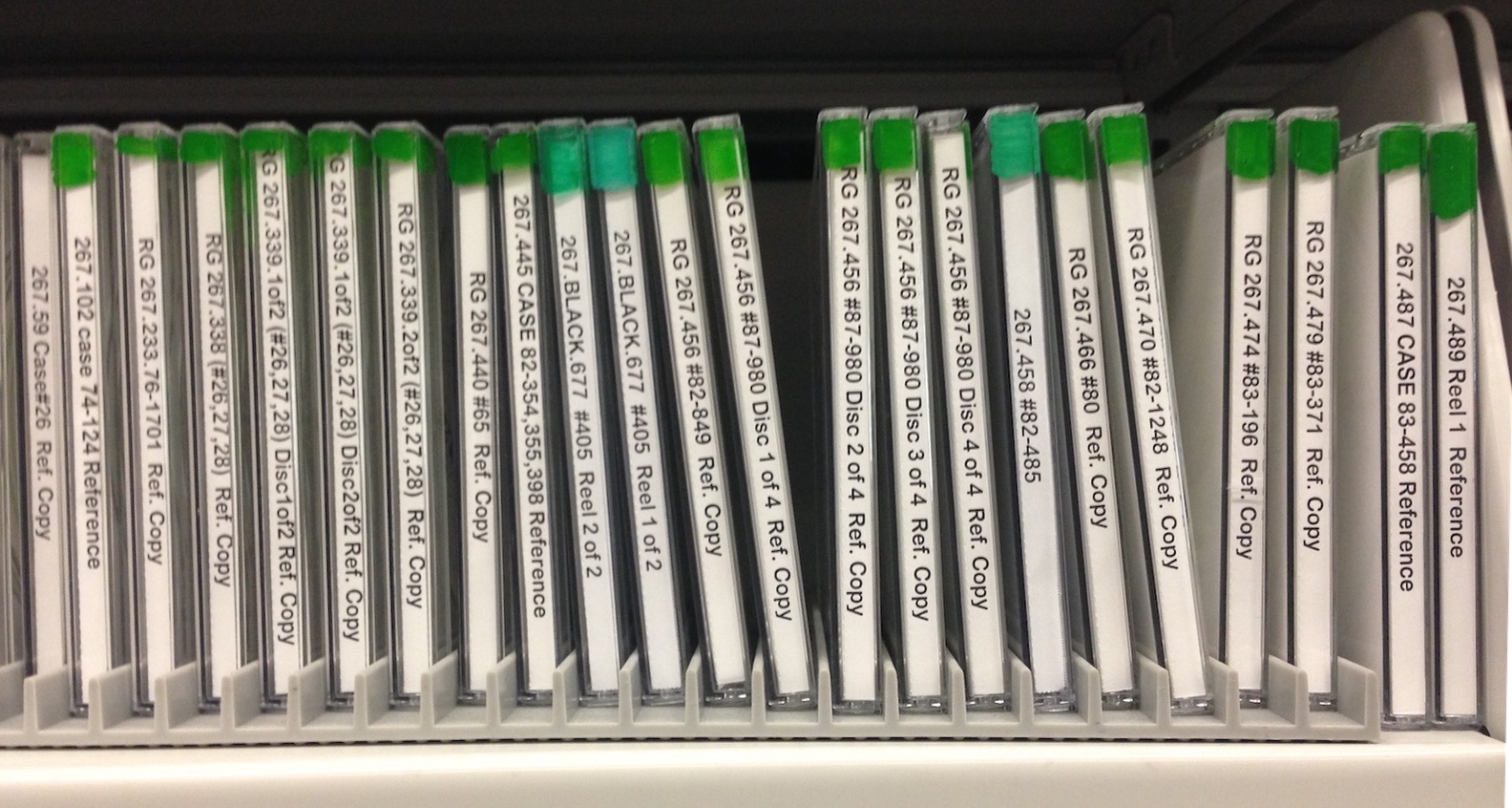

If someone wants a copy of anything on those tapes, they have to fill out a form and wait for the archives to produce a reference or “shelf” copy. In the old days, those reference copies would be reel-to-reel tapes. As technology progressed, cassette tapes were used to hold reference copies, and more recently, audio CDs.

However, if you’re lucky and someone else has already requested a tape you’re interested in, then a reference copy may already be sitting on the shelf. For example, in March 2014, I had to request a reference copy of Keeton v. Hustler Magazine, as no shelf copy was available. A few weeks later, when I visited the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, NARA staff had added the CD to the compact stacks, and I was able to copy the audio onto my laptop. And now anyone else who wants that particular audio recording can do the same.

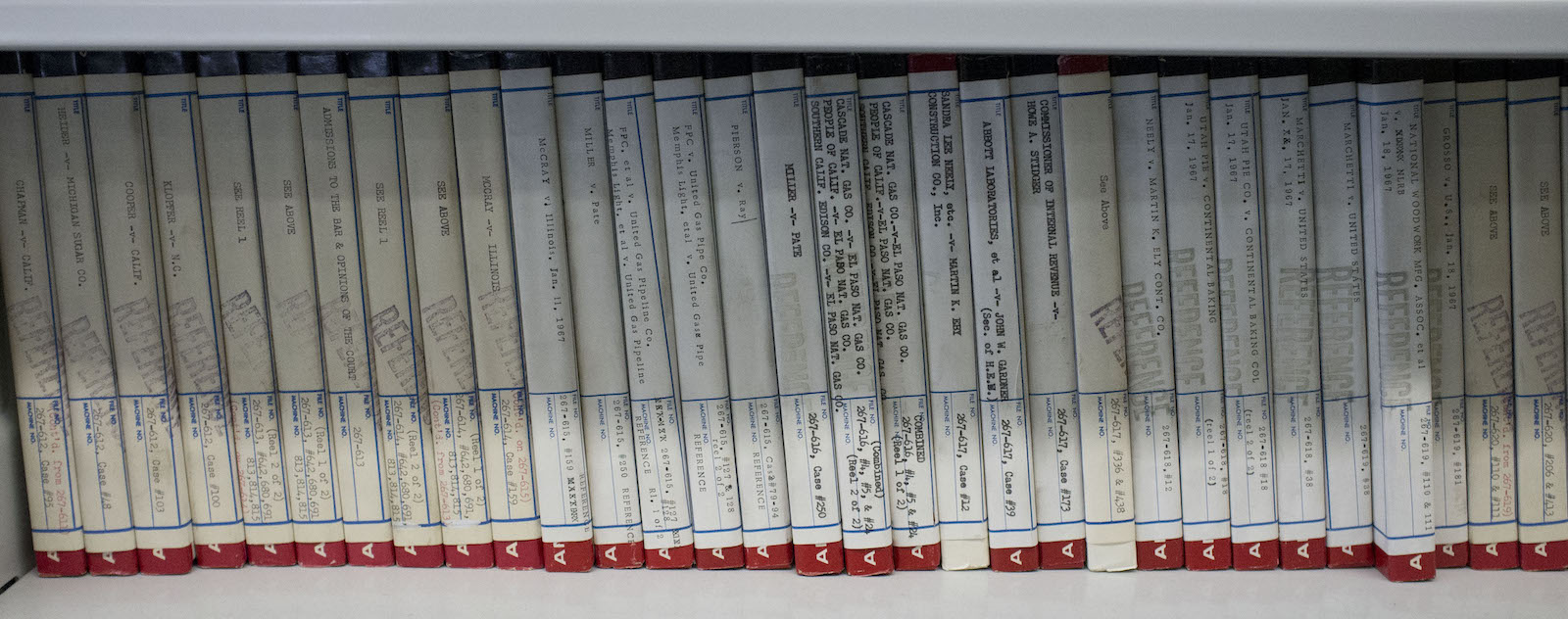

In fact, most Supreme Court recordings from 1955 into the 1970s are currently available on reel-to-reel reference tapes at College Park, sitting on shelves in compact stacks for anyone to access – but not because someone had previously requested them all. Decades ago, when NARA was probably better funded, they undertook a massive effort to duplicate all the original tapes, producing new masters, and then cutting and relabeling the original tapes to produce what are now called reference or shelf copies.

So, when you pick up a Supreme Court audio tape from the 1950s or 1960s off the shelves at NARA, you are holding an original tape, not a copy. Here’s a snapshot of one of the many rows of such tapes.

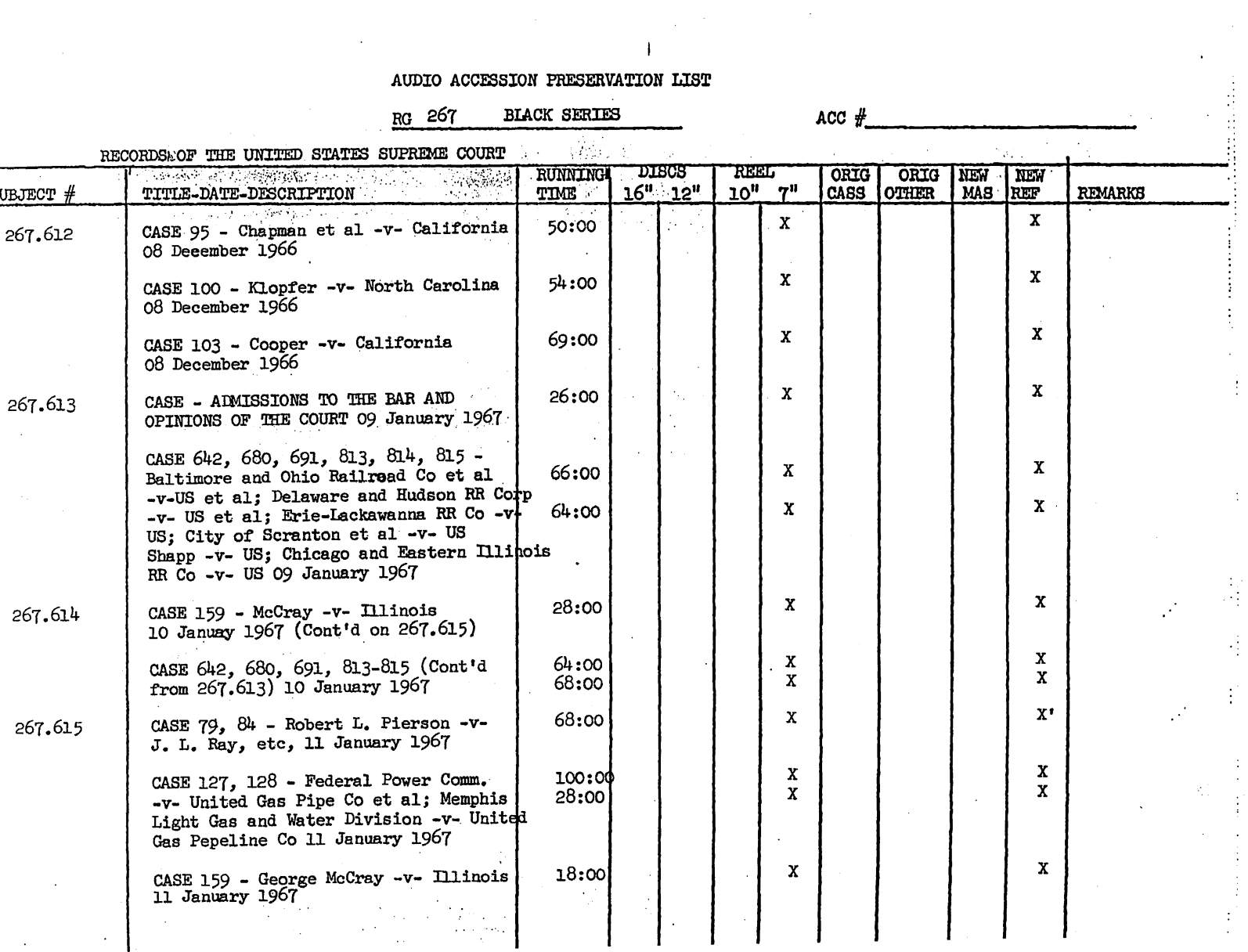

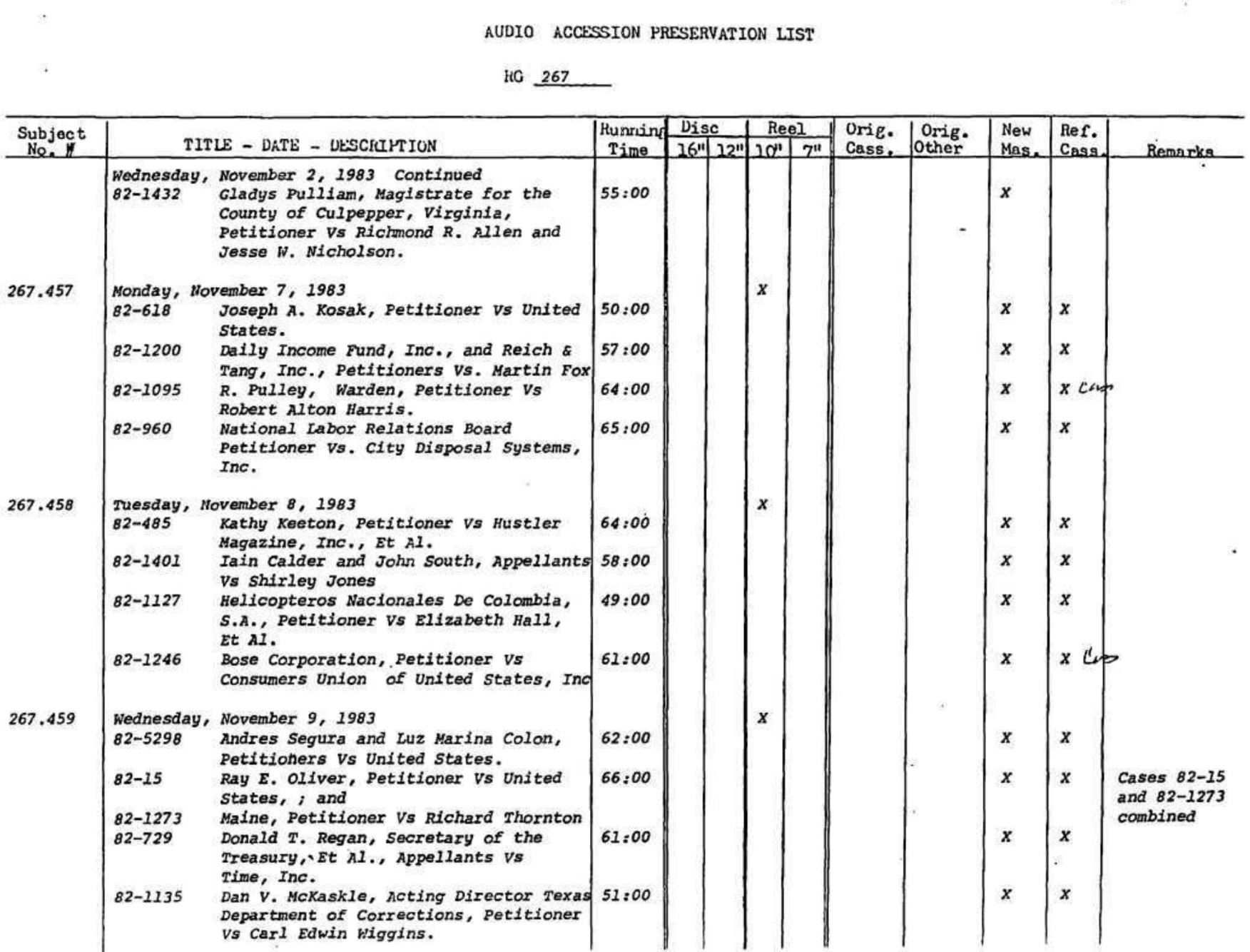

Near the tapes are binders containing Accession Lists that can help you locate tapes you’re interested in. Unfortunately, the descriptions are not always sufficient. For example, the Court would occasionally record opinion announcements in the 1950s and 1960s, but it was rarely and sporadically done, and no one noted which opinions had been recorded. Sometimes you must cross-reference the dates with your own lists of Court activity.

Back in 2007, when I mounted tape 267.613 labeled “ADMISSIONS TO THE BAR & OPINIONS OF THE COURT”, I discovered that a rather important opinion announcement, Time, Inc. v. Hill, had been recorded. I duplicated it and passed it on to The Oyez Project, which at the time, was missing that particular recording.

About That Keeton v. Hustler Recording

As I mentioned earlier, there didn’t used to be a reference copy of Keeton v. Hustler, so I had to submit a copy request to NARA identifying the recording. Keeton was listed in Record Group 267, Item Number 267.458, Case Number 82-485.

As you can see below, once the reference copy is generated, NARA shelves it chronologically with the rest of the randomly requested reference copies. Their labeling standards have changed slightly over the years, and you’re also at the mercy of sloppy researchers reshelving a reference tape/cassette/CD in the wrong location, but in general, things are where they’re supposed to be.

When you finally get the recording, you’ll often find other material recorded both before and after the actual oral argument. For example, in Keeton, you can hear the Marshal’s traditional “Oyez Oyez Oyez” opening, followed by a handful of admissions to the Supreme Court Bar.

The rest of the Keeton argument can be found on the Oyez website. You’ll notice that Oyez generally trims all their recordings to just the argument or the opinion, so you won’t hear the audio above in their copy.

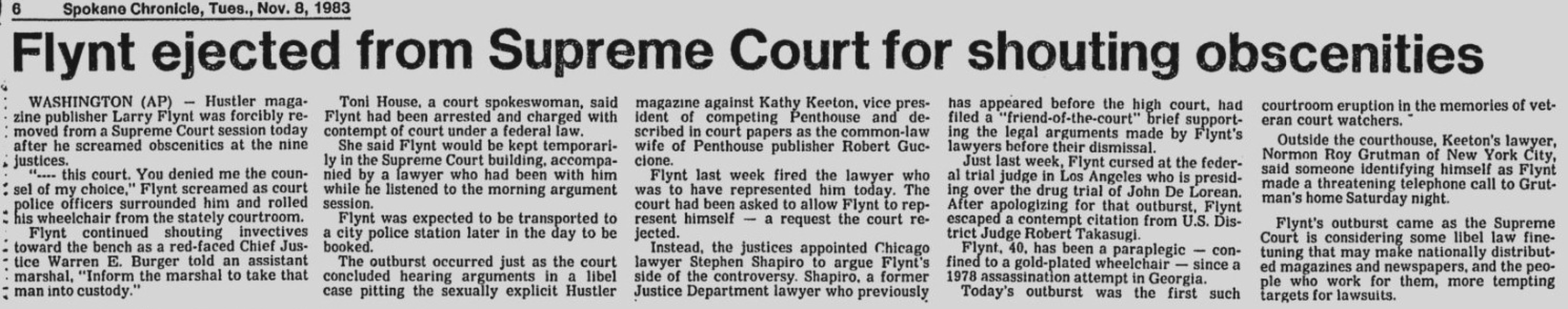

What’s also interesting about the Keeton case is that, reportedly, Larry Flynt made an obscene outburst at the conclusion of the argument. Whatever transpired, however, didn’t get picked up by the Court’s microphones.

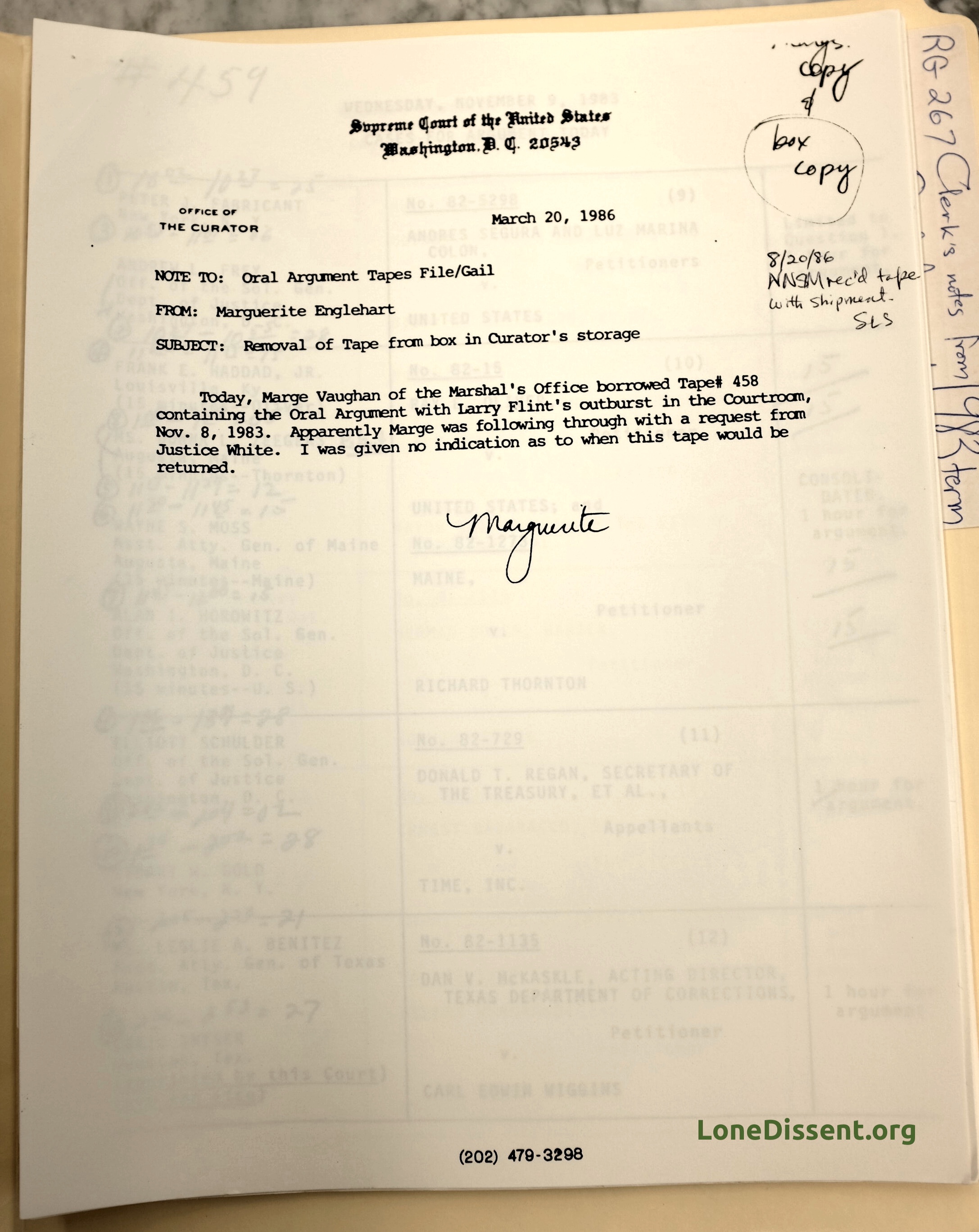

The incident may have piqued the interest of Justice White a few years later, because I also found the following correspondence in the archives, stashed among all the Day Call sheets.